A speech by Mr. Laki Vingas, the Representative of the Minority Foundations at the General Directorate of Foundations Assembly, delivered at the conference, “Vienna-Istanbul 2010: Crossroads of Faiths and Cultures in Turkey” held at the Austrian Consulate, Yenikoy on 12 October 2010.

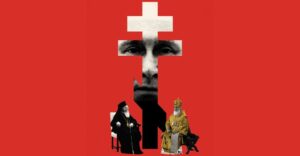

“The minority foundations in Turkey and their role as cultural bridges”

Somewhat untidily subsumed within the walls of the churches of Saint Dimitrios, patron saint of Thessaloniki, and of St George in the same city, are the remains of Jewish funeral monuments, Roman marbles, and Byzantine inscriptions. The Sinopi prison, on the Black Sea, is partially built with blocks of stone cut in the Roman era. It has been said that the magnificent mosque of Suleyman the Lawgiver, which stands imposingly over the Golden Horn, used stones taken from the church of Saint Effimia in Kadikoy.

Wherever one might roam, in the Balkans or in Anatolia, he will stumble on the traces of the three great civilizations that have succeeded each other in the region, the traces of which are inextricably interwoven. In this corner of the Earth, both stones and memories demonstrate a remarkable adaptability, thus resisting time and deterioration.

Both their longevity and their surprising freshness are due to their boundless ability to adapt to new conditions, just as water will flow, find an outlet and circumvent the dam. One need not be either particularly wise or expert to see and trace, in every corner of Turkey, the multitude of witnesses to a long and storied past. For her current residents, they have the same value as the rich river silt, deposited in the fields after a long and winding journey, has for the farmer. The charitable foundations of the non Muslim minorities of Turkey are but tiny pieces in a vast, rich mosaic. Although their role and function have changed considerably over the past few decades, they still represent valuable elements not only for the cultural continuity of Turkish society, but also for its advancement and development.

In the Ottoman era, schools, places of worship (including Christian churches and Jewish synagogues), hospitals, philanthropic institutions and orphanages were founded to serve the needs of the large Christian and Jewish communities which lived in the territory ruled by the Sultan. As early as the period of Ottoman conquest in the 15th century, the religious identity of the populations of the Empire was one of the basic pillars on which the administration of the State was built. Until the end of the First World War, Ottoman citizens were formally defined as either Muslim or non-Muslim. The former were subject to the direct supervision and protection of the state authorities. The latter communities, both Christian and Jewish, were given the right to order the social and community life of their co-religionists as they saw fit. This autonomy was formalized in the 19th century with the adoption of the General Regulations (Nizamname) of the various millets. Within this framework, while still ultimately subject to the authority of the Ottoman state, non Muslims were permitted to set expound and implement their own educational programs, to equip their hospitals, and to build and maintain houses of worship. Furthermore, they had the right to appeal to their various religious authorities to resolve disputes involving family matters, including marriage, divorce and inheritance.

Nonetheless, in practice, these separations were never quite so absolute. In the Christian Orthodox hospital of Baloukli, the Armenian hospital Surp Pirginc and the Jewish hospital Or-Ahayim in Istanbul, neither the doctors nor the patients were exclusively Christian or Jew. On the student lists of the minority schools, Muslim names are few, but present. In the neighborhoods of the Golden Horn, Muslims were ever present at the Christian festivals in honor of Saint George and Saint Dimitrios, as they continue to pour the Monastery on the hill of Buyukada (Prigipos) on the day of Saint George every year. In outlying areas like Thessaloniki, the records of the kadis contain, up until the very end of the Ottoman era, cases where for some reason Christians and Jew preferred to avoid the jurisdiction of their ecclesiastical or rabbinical authorities. In other words, the bridges and crossings, and by extension the effects on each other, among the Ottoman subjects of all religions were both various and frequent.

The national states which followed the Ottoman Empire demolished this polyphony. For their stability and survival, they chose the path of cultural homogeneity — a logic diametrically opposed to that espoused by the great empires. Structurally, cultural homogeneity implies a common religion, language and collective historical memory. In order to achieve this superseding goal of uniform nations, in the decades following the 1920s, each of the states of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Turkey undertook the Hellenization, Bulgarification, Serbification, and Turkification of those populations who happened to be living within its territorial borders. At the same time, each nation neglected to exploit the surviving witnesses of another ethnic, religious or other past history. For proof, we need only to look to the hundreds of Ottoman monuments scattered throughout the Balkans — how many of them are accessible to the public and preserved as historical memorials? Accordingly the hundreds Christian monuments scattered in Anatolia are being left in their fate as was stated this morning by the Armenian and Syriac bishops.

For Turkey, in the throes of constructing an ethnically uniform nation state, the insistence on “Turkishness” combined with other political and economic factors caused the 20th century to be marked by the mass exodus of non-Muslims — any who had remained following the Turkish struggle for independence. Thereafter, the combined factors of the 2nd World War and the necessary reconstruction of a shattered Europe, together with the optimism that often follows the end of armed conflict and Turkey’s inward-looking economic policy, spurred the huge emigration waves of the second half of the 20th century. In addition to the significant economic factors that encouraged emigration on the part of Turkish citizens of all religions, it must be noted that the remaining non-Muslims had even greater incentives to abandon their homeland. Not only did the state do nothing to discourage their departure, but it took a series of measures specifically designed to marginalize and eliminate all those who maintained their minority identity and did not adopt the Turkish identity wholesale. It is not necessary here to detail those measures that caused such grave wounds to the minorities, and which are so profoundly seared into the collective subconscious that the prospect of healing is nearly impossible to imagine.

What, then is the result? In today’s Turkey, the non-Muslim minorities are so reduced in population that it is difficult to even speak of them as constituting “communities”. Nonetheless, those individuals who remain are the undisputable guardians of a profound and ancient cultural heritage which constitutes, whether we like it or not, an indivisible part of Turkey’s collective historical memory. The hospitals, the Christian churches, the Jewish synagogues, the cemeteries, the nursing homes, and the schools are no longer in a position to fulfill the mission for which they were founded. Many churches and synagogues are empty, the cemeteries “inoperative”, the schools serving greatly diminished populations.

Somewhat paradoxically, the current situation represents an extraordinary opportunity for Turkey to demonstrate once again the flexibility and resilience of the elements of the historical legacy of the Eastern Mediterranean. Although they have lost many of their original elements, the vakifs/foundations of the minorities are nonetheless incontrovertible evidence of the cultural polyphony of past centuries. In Istanbul particularly, they can once again play an important role in the formation of an urban identity by the numerous residents who have come from rural or agrarian areas. In any major Turkish city today, a significant portion of the population is made up of the internal economic migrants of the last few decades. Most of them have no connection to the collective historical memory of the places where they now reside, and yet, they are here to stay. Their successful assimilation into the urban culture, as well as their potential for socioeconomic advancement, is in part dependent on their ability to develop an urban consciousness. In this area, the revitalization of the minority vakifs, in a manner devised in common by the state authorities and the representatives of the minorities, could very well contribute to the stabilization of the urban populations. Such a move would also provide support for the long-held position, propounded by the intellectuals of this country, with respect to the tolerance of the Ottoman sultans and their legitimate inheritors of political power towards the non-Muslim communities. The revitalization of the minority institutions within the Turkish state, adapted for current times and conditions, would establish Turkey once and for all as a country open to differences, while at the same time certifying the success of the nation-building effort.

The new law, in force since February 2008, respecting the functioning of the “vakif”, does not satisfy all the demands of the minorities and leaves some matters pending. Nevertheless, it has implemented fundamental changes and an indisputable “loosening” of the legal framework concerning the foundations. This liberalization gives, among other things, the right to the institutions to develop broad spectrum programs of social and educational policy which do not restrict themselves strictly to the needs of the specific minority, but which may contribute to the overall economic development of their region. One proud example is the Halki Music School being established under the direction of Nikiforos Metaxas and with the full participation of the local authorities (Adalar Belediyesi), which is expected to invigorate the cultural and touristic activity on the Princes’ Islands. The success of this venture will be beneficial to all local residents, not just those of the Christian Orthodox minority. Another similar example constitutes the undergoing project which will be realized with the support of the Agency for Istanbul Cultural Capital of Europe 2010 whereby the Armenian Vortvots Vorodman Church will be restored and renovated in order to become an exhibition-conference hall with the aim to boost awareness about being a part of urban life and to add a meaningful visiting spot on the culture and tourism map of the city. Likewise the Mayor Synagogue in Haskoy underwent a restoration and was used for cultural events during this year, in the framework of the celebrations for Cultural Capital 2010, representing in this way an identity which is cherished with its all historic components. Similarly, the Greek minority school of Ferikoy, inactive today, served as one of the venues of the Istanbul Bienale of 2009. The cultural events and educational programs that may now be established with the initiative of the minority institutions are an unquestionable channel of communication between the new generation and the presence of the minority communities in Turkey’s recent history. Although the full effects of this legislation have not been felt, it is already apparent that it has served to encourage the communication among the minority communities’ members. Thanks to the “vakif”, Armenians, Greek Orthodox, Jews and Syrian Christians now sit around the same table, exchanging views and planning for the future on a common playing field. This synergy in also extended in cities like Kayseri, Elazig, Adiyaman, Diyarbakir, Mardin, Hatay, Mersin and Canakkale where the members the minorities are few but their foundations still represent a valuable element in the city landscape.

In other words, encouraging the participation of the individuals who represent the minorities in the conscientious exploitation of their foundations could serve to soften the rigidity of the traditional divisions and differentiations along religious lines — the excuse for so many crises and so much harm in this long-suffering region. The elimination of discrimination for religious reasons is, in the current era of globalization, a necessary precedent so that Turkey does not lose the pivotal role of mediator which is offered on the new geopolitical chessboard. Finally, leaving aside the theoretical issues of international politics, a new and dynamic role for the minority institutions would allow their members to take their places as full Turkish citizens in modern Turkish society, without the subtly negative designation as “minority.”