By John Thavis

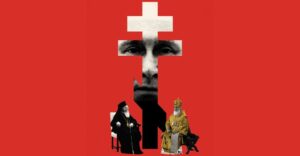

ROME (CNS) — Global interest in Pope Benedict XVI’s upcoming trip to Turkey has focused on relations with Muslims, especially after the pope’s recent remarks on Islam and the controversy that followed.

But the Nov. 28-Dec. 1 visit also will highlight the tiny but historic Greek Orthodox community in Turkey and its struggle for religious freedom.

In fact, it was Istanbul-based Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew who first invited the pope to visit as a demonstration of ongoing dialogue between the Christians of East and West — an aspect overshadowed by the latest controversy with Islam.

In an apparent desire to put ecumenical relations and Christian issues back on the map, Patriarch Bartholomew recently held meetings with reporters, outlining his expectations for the papal trip.

“We are awaiting the pope’s visit with fraternal love and great anticipation. It will be very important for our country and for Catholic-Orthodox relations,” the patriarch said in late September.

The tentative papal program includes several events hosted by the ecumenical patriarchate: vespers, a Divine Liturgy, private talks between the pope and the patriarch, and the signing of a joint ecumenical declaration.

In these and other encounters, the Orthodox are hoping the pope will raise the profile of their minority church in Turkey and provide public support for their religious rights.

“The pope always underlines the principles of religious freedom and human rights … which are valid principles for democratic societies. So I think the pope in his sermon here will speak not only in favor of Catholics but in favor of all religious minorities,” Patriarch Bartholomew said.

The ecumenical patriarch holds a place of special honor among the world’s Orthodox leaders. His flock in Turkey, however, numbers only about 5,000 ethnic Greeks today, following a long exodus of Greek Christians over the last century. In 1923, when the modern Turkish state was founded, the country had an estimated 180,000 Greek Orthodox.

The patriarch could pack up and move to Greece, but he has remained, noting that the patriarchate has been located in Constantinople — the traditional name for Istanbul — since the fourth century. In fact, over the last decade Patriarch Bartholomew has been rebuilding his church’s headquarters in the Phanar district of Istanbul and expanding its activities.

But the future of the Orthodox Church in Turkey is clouded by a number of government policies. For one thing, the ecumenical patriarch must be a Turkish citizen, a requirement that Patriarch Bartholomew has tried unsuccessfully to have modified. The Orthodox want to be able to elect a leader from the church’s wider membership, in countries ranging from South Korea to the United States.

Perhaps the most visible church-state issue in Turkey is the patriarchate’s attempts to reopen its seminary on the Turkish island of Heybeli — better known among the Orthodox by its Greek name, Halki. The Halki school was renowned for centuries as an institute of learning, but was closed by the government in 1971 as part of a general decree against private religious colleges.

Today, the seminary’s classrooms are empty and its hallways are silent, except for the echoing footsteps of three monks assigned to maintain the premises.

“In closing this school, the government of Turkey has acted against the principles of religious freedom and human rights,” Patriarch Bartholomew said.

“The ecumenical patriarchate is the first see in the Orthodox world, and yet it is the only independent Orthodox church that has no theological school to prepare its theologians and its clerics. For us, this is unacceptable; it’s an injustice,” the patriarch said.

Despite pressure from the European Union and past U.S. administrations, the Turkish government has given no sign of relenting on the closure of the Halki school.

One of the clerics who stays at Halki, Deacon Dorotheus, gave reporters a tour of the vacant premises in late September. He gestured with pride at the library’s shelves full of ancient books and manuscripts, which few if any students are able to use.

Deacon Dorotheus explained that, in his view, the academy’s closure may have as much to do with Islam as with Christianity. He said those responsible for Turkey’s internal security see private religious schools as a threat to the secular state.

“If permission is given for this school to reopen, some fanatics of Islam may want to open their own private religious schools. I hope I am mistaken, because if I am not mistaken we will have to wait another 35 years to reopen this school,” Deacon Dorotheus said.

The patriarchate has had other properties, including a historic orphanage, confiscated by the state.

The Orthodox church has pinned most of its hopes for religious rights on the possible entry of Turkey into the European Union, which it believes will help give minority religions some political leverage.

“Regarding the problems for our community and for other religious minorities in Turkey, we nurture the hope that Turkey’s ‘European process’ will resolve them one after another,” Patriarch Bartholomew said.

“The members of the European Union are asking our country to respect these (religious) principles and rights, and I think a lay, democratic state like Turkey should respect and apply them,” the patriarch said.

But so far, the Turkish government has shown little response to European pressure on the Orthodox church issues. And, in a development that worries the country’s Christians, support for EU entry has plummeted in recent months among the Turkish population.

While the Orthodox expect Pope Benedict to defend religious freedom, the pope’s own views on Turkish admission to the European Union complicate the issue. As a cardinal, he spoke out against Turkish entry, saying it did not make historical sense; since his election as pope, however, the Vatican has been careful to emphasize its neutrality on the question.

Even as the focus of the papal visit has shifted to Islam, Orthodox leaders say the Christian unity aspect of the trip remains crucial.

Deacon Ioakim, 34, who follows legal issues at the patriarchate, said the pope’s presence will underline his church’s ties with global Christianity. He said he expects the pope’s words about the minority Christian community in Turkey to carry some weight.

“After all, he is not just any visitor. He is the head of the Roman Catholic Church,” he said.

Copyright (c) 2006 Catholic News Service/USCCB. All rights reserved.