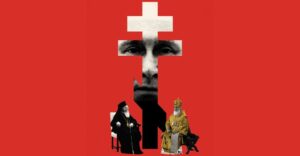

Megali Evdomada (Orthodox Holy Week), with its ancient rituals and ancestral symbols, has just passed. The Byzantine Easter troparion, sung three times in the fifth tone, says: “Christ, by dying, has conquered death.” Yet the mystical vocation and stubborn preservation of the Orthodox Church’s ancient rituals should not lead us to believe that it is just a conservative backwater. It would be wrong to underestimate the theological modernity of its worldview, simply based on the fact that it has traditionally shied from exercising temporal power or on its low-key political lobbying, compared to the brasher approach of the Catholic Church. This is particularly obvious in the religious mission of His All-Holiness Bartholomew, Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople for twenty-two years and spiritual leader of the Orthodox worldwide.

During his visit to Italy for the commemoration of the 1700th anniversary of the Edict of Toleration of 313, he granted us an interview centered on the idea of freedom, as a tribute, he wanted to make it clear, to religious freedom “expressed as a concept, for the first time in human history, by Constantine the Great.”

But “freedom” is a challenging word for Bartholomew: “Freedom is a deep mystery, eternal and unfathomable.” He quotes John Chrysostom, his fourth-century predecessora s Archbishop of Constantinople: “It shines in slavery.” He then looks at us with his blue eyes: “This is testified by the seventeen centuries in which the Ecumenical Patriarchate has lived in earthly bondage, albeit free, indomitable and unsubdued in thought and spirit.” So can we do without political freedom? He responds: “Freedom is one of the most ill-treated goods in history. It has been overly talked about in the 19th and 20th centuries. Two world wars have been fought in the name of peoples’ so-called freedom, which was generally identified with conflicting ideologies. Freedom has thus been idealised, taking on a human-centred outlook and becoming all-powerful. A great many crimes have been committed in the name of this kind of freedom; even the Russian Revolution was followed by the millions of victims of the Stalinist regime. In society, this libertarian surrogate degenerates into another form of mystification: a kind of deceptive freedom, which satisfies human desires and individual needs, while debasing the human person to a lower level of existence. Few people actually know what true freedom is all about and where it can be found.”

Where? “At the time of the October Revolution a student went to visit the great ascetic Silouan on Mount Athos; they talked for a while. At that time, there was a pressing and imperative demand for freedom. The young man’s ideas focused on both the quest for greater political freedom and a general ambition to accomplish his desires.” Silouan said to him: “Who does not desire freedom? Everyone wants it, but you must know where to look for it. And how can you find it? By binding yourself. The more you bind yourself, the freer your spirit will become.” Bartholomew remains silent for a moment. “No one can be free until he stops worshiping his ego. The model of perfect freedom is kenosis, the self-emptying of one’s will,” proposed to us by St. Paul in his First Letter to the Corinthians. “A human being is free when he or she achieves the purification, when one denies oneself for the other. True freedom, then, is found in love.”

“Love, and do what you will,” says St. Augustine. We are only free when we love. But in today’s society, dominated as it is by claims, demands and rights, humanity is unable to understand the meaning of true freedom as love. The only freedom that human beings can achieve is liberation from the worship of the idol of oneself, which was precisely what was sanctioned by Constantine the Great. Otherwise, we return to idolatry, even though we have progressed, though we may fly to outer space, and though we believe that science and technology can “work miracles.”

We ask him about today and his position on the so-called “clash of civilizations” is very clear. “There are no religious grounds for a violent confrontation between the cultures and principles of Christianity and Islam. This theory has no basis whatsoever, to the extent that it posits religion as the motive force behind a so-called clash. But when the aspirations of nations and geopolitical circumstances lead to external or internal conflicts between peoples, and religion places itself at the service of politicians to strengthen hostility and the idea of diversity, then it is an entirely different matter.” Bartholomew is alluding to the Middle East and the civil war in Syria. “Hatred and intolerance are ravaging the Middle Eastern countries, which are experiencing regime changes, revolutions, and wars sparked by the demand for more freedom and democracy. Religious violence stems from these conflicts. In Syria, Christians of all denominations, clergy and laity, despite all efforts to remain neutral, are continuously kidnapped and murdered. But we spiritual leaders must do all that we can to prevent such developments by softening the ethnic, economic, and ideological differences. True freedom dissolves all prejudices; it is an opportunity to overcome our limitations. True freedom liberates the spirit from one-sidedness.”

Yet some people are prepared even to face death in order to assert their religious convictions. “Many are so attached to their convictions that they prefer to sacrifice their life rather than change them. Of course, the solution does not lie in trying to change them. Instead, it may be found in looking deeper into these convictions. The more we pursue truth, the more we realise that seemingly contradictory and incompatible visions can actually concur and coincide with one another. The Gospel says: “Whoever would save his life will lose it.” Many of our fellow human beings lock themselves inside spiritual and ideological strongholds to preserve their spiritual integrity. However, they do so in vain. They will understand, in time, that the more they try to protect themselves, the more stressful their life becomes because no fortress can withstand the strength of ideas. There is a Greek word, metanoia, which translates as repentance or conversion, but which literally means ‘change of mind, a transformation of mentality.’ It is not a question of religious conversion, though every human being is absolutely entitled to this. On the contrary, it is a journey towards mutual understanding and assimilating diversity.”

Therefore, towards philosophy? “Heraclitus considered Hesiod a ‘teacher of humanity’ because of his failure to distinguish between night and day. It takes great spiritual courage and an ability to transcend the perceptions of the ordinary person in order to claim that these are ‘one and the same thing.’ But if we look deeper, we will realise that Hesiod was correct, while those who mocked him were wrong. If only modern man would look deeper into things, he would find that his deepest being, the dismissed voice of his conscience, recognises the unity of even those things that appear divided. The differences between slave and free, woman and man, man and man, whatever tribe, language and religion they belong (Greek or Latin, Islamic or Jewish) are fewer than the differences between day and night.”

Do you love classical Greece? “The enormous development of the Greek spirit during the classical period was due to the ability of the Greeks to blend their ideas with those of other peoples and civilizations, absorbing with admirable discernment all the good that they encountered outside Hellenism and reformulating this in a new vision. This freedom of spirit is the basis of all progress, both material and spiritual.”

Regarding progress, what is your opinion on the status of the embryo, about which the Pope has recently spoken? “The Orthodox Church is interested in cultivating the conscience of human beings in order for them to make their existence useful to civil society. Our task is to form consciences so that they can grow freely and be mutually respectful; their peaceful coexistence can help the spiritual promotion of human existence, and it is this spiritual promotion that is of interest to the Church. It is up to the State to legislate on anything that goes beyond this. Having said this, however, the enlightened person is always in search of divine justice.” And on transplants? “I cannot help thinking of that Palestinian father, who donated the organs of his son, killed by the Israelis, to an Israeli hospital, for them to be transplanted into the body of another young man, regardless of whether he was Israeli or Palestinian. I think that, on that day, a bright beam of light shone in the sky.”