By SUSAN SACHS (NYT)

Published: November 21, 2004

In the cavernous Panayia church, one of the few Greek Orthodox churches still active in Turkey, ceiling panels dangle precariously over the choir loft. Flying glass has pitted the frescos of biblical scenes. Musty carpets are rolled up and stored like logs beside the elaborate Byzantine iconostasis.

The building, which celebrates its 200th anniversary on Sunday, has been scarred for a year, since terrorists bombed the nearby British Consulate and the force of the explosion shattered dozens of the church’s stained glass windows.

Orthodox leaders, following Turkish law, asked for government permission to make repairs but received no response. Rain seeped in. Paint peeled. Mildew grew.

After a few months, they surreptitiously replaced the broken church windows. But they hesitate to start renovations because the Turkish authorities, as frequently happens in such cases, still have not acknowledged their request.

”That’s the usual tactic,” said Andrea Rombopoulos, a parishioner who publishes a newspaper for the small Greek Orthodox community in Istanbul. ”They don’t give a negative answer. They don’t give any answer at all.”

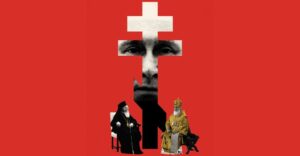

Turkey has long viewed its non-Muslim minorities with a certain ambivalence, defending individual freedom of worship while tightly regulating the affairs of religious institutions. Christians of Greek and Armenian descent, in particular, have said they are blocked from using, selling and renovating properties that have been in their churches’ hands for centuries.

Now, under pressure from the European Union and local civil rights advocates, Turkey has started to cautiously reassess the way it has treated religious minorities since the state was founded 81 years ago.

Prime Minister Recip Tayyip Erdogan’s government has prepared legislation that would give Christian and Jewish foundations more freedom to manage their own assets and elect their board members. Parliament is expected to vote on the bill before Dec. 17, when European Union leaders are to decide whether to open accession talks with Turkey.

For the first time, senior Turkish officials have also broken a long-standing taboo and broached the idea of allowing the Greek Orthodox patriarchate to reopen a 160-year-old seminary that once served as a leading training center for priests.

The school, perched on a hill on an island in the Sea of Marmara off Istanbul, was closed in 1971 when the state took control of all private universities. Mr. Erdogan’s aides have suggested that it could be permitted to operate again, as a gesture to the European Union, if Turkey’s membership bid advances.

Some legal constraints on religious foundations have already been relaxed over the past three years, although European and American human rights monitors, citing cases like the Panayia church, have reported that local officials have been reluctant to carry out the changes.

Still, Christian leaders here said they were more hopeful than ever.

”What has changed is that we don’t have that hostility anymore from the authorities,” said Elpidoforos Lambriniadis, an aide to the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew. ”As the patriarchate, we don’t doubt the good will of the government. But we know the government is not controlling everything in this country.”

For many Turks, even a discussion of religious or ethnic minorities raises fears of separatism. Some have argued that lifting government controls on religious institutions, whether Muslim or non-Muslim, would undermine Turkey’s secular foundations. And Turkey’s president, Ahmet Necdet Sezer, recently warned that drawing attention to Turkey’s sectarian or cultural diversity harmed the state.

The delicacy of the issue was highlighted earlier this month when a government-sponsored commission released a report criticizing Turkey’s definition of itself as a ”single-culture nation-state” and urging an end to all restrictions on the expression of minority languages and cultures.

When the report was presented at a news conference, a dissenting member of the commission ripped a copy from the hands of the presenter and tore it up. Later, the Erdogan government, which established the commission, also disowned it.

Baskin Oran, the Ankara political science professor who headed the commission, said he was undeterred by the reaction.

”They are clearly seeing that what they have been pushing under the carpet since the 1920’s is now being questioned,” he said, ”Now, everything will be discussed. There will be no taboos in Turkey, and they hate that.”

For some hard-line nationalists, even the term ”minority” is anathema, suggesting dual loyalties and the betrayal of the country’s cherished ideal of an indivisible Turkish identity.

”In the end, there will be lots of small groups feeling different and trying to identify their differences as separate identities on basis of religion, race or language,” said Mehmet Sandir, a spokesman for the Nationalist Movement party. ”And at times of economic or political crisis, our country will immediately turn into a ‘minority hell’ of internal strife.”

Turkey’s enemies, he added, could then exploit those differences to split the nation, as the European allies and Russia did after World War I when the Ottoman Empire was further divided.

”This is not paranoia,” said Mr. Sandir, whose party has organized demonstrations against the orthodox patriarchate. ”The recognition of minorities was used as an argument in destroying empires. The Balkans are boiling now because of this chaos of minorities.”

A distrust of minorities is drilled into Turks from childhood, according to Hrank Dink, a magazine publisher and scholar active in the country’s ethnic Armenian community.

”In public school, ‘minorities’ are mentioned in the textbook on national security, under the section that talks about separatism and about the ‘games played against Turkey’ by outside powers,” Mr. Dink said.

That suspicion carries over to the local officials who are in charge of regulating the non-Muslim religious foundations, including those that administer the 17 schools and 42 churches of the Armenian community in Turkey.

”They see the minorities in terms of national security,” Mr. Dink said. ”The fewer there are, the less they feel threatened.”

The official doctrine on minorities stems from the 1923 Lausanne treaty in which the European powers recognized Turkey’s independence and received guarantees concerning the status of three non-Muslim communities — Jewish, Greek Orthodox and Armenian — in the new and predominantly Muslim Turkish state.

The three groups mentioned in the treaty, sometimes referred to as ”indigenous foreigners” in official documents, were promised protection but not the privileges they enjoyed under Ottoman rule.

The Greek Orthodox patriarchate, regarded with great suspicion by the Turkish leaders because of its support for the failed Greek invasion a few years earlier, was allowed to remain in Istanbul, where it had been based for nearly 1,700 years.

But Turkey did not recognize its ecumenical authority, instead treating successive Orthodox patriarchs as parish priests responsible for the churches in their immediate neighborhood.

The treaty did not mention Turkey’s minority Alewite population, who are Muslims but follow a different sect from Turkey’s Sunni mainstream and now want their national identity cards to show them as Alewite instead of Muslim.

Nor did the treaty mention ethnic minorities like Kurds. Until recently, Turkish governments used that omission to justify their ban on references to Kurds as a distinct subgroup in Turkey. The government has eased its restrictions on Kurds in the past two years but it refers to them as a group using a different language than Turkish, not as a minority.

More changes are inevitable, said Professor Oran, who spearheaded the government report on minorities.

”The concept of ‘minority’ has changed since the Lausanne Treaty,” he said. ”Now it’s anyone different from the majority and who wants to maintain this difference. We have to delete the laws that prevent them from using the same rights as the majority. If a Turk can read and write and publish in Turkish, then any Kurd or Circassian should have the same right.”

”The genie,” Professor Oran added, ”is out of the bottle.”