This article first appeared on ahramonline

A US State Department report on religious freedom and a warning early this week left Turkey unhappy. But not wrongly accused, say many. Nora Koloyan-Keuhnelian reports

In our modern world, most of the peoples and nations living on Earth seek to live in harmony and peace. But seemingly not Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

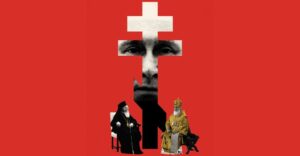

Last week, a Turkish court heard a petition seeking to convert the Hagia Sophia museum back into a mosque, over which the US State Department issued a statement urging Turkey not to do so. Considered a symbol of religious tolerance and cultural diversity, being a mix of Christian Byzantine and Ottoman Empire architecture and historical richness, the Haiga Sophia museum was chosen a world heritage site by the UNESCO in 1985.

Earlier last month, the US State Department issued its 2019 Report on International Religious Freedom. “It is written in a language far from objectivity,” was the Turkish Foreign Ministry’s curt description of the report’s contents on Turkey. In a statement 1 July, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo urged Turkey “to continue to maintain the Hagia Sophia as a museum, as an exemplar of its commitment to respect the faith traditions and diverse history that contributed to the Republic of Turkey, and to ensure it remains accessible to all.”

The US State Department sees any change in the status of the museum as diminishing the legacy of this remarkable building and its ability to serve humanity as a much-needed bridge between those of different faiths and cultures. “It is a testament to religious expression and to artistic and technical genius, reflected in its rich and complex 1,500-year history,” Pompeo’s statement read.

“It is not surprising that Turkey ignores or denies the findings in the US religious freedom report, because what the civilised world sees as a violation, abuse or crime, Turkey sees as a normal and even a glorified action. We see the usurpation of churches and their conversion into mosques or other types of facilities as an insult to human rights and religious freedom. But NATO, UN and Council of Europe member Turkey has turned the violation of human rights into a proud tradition,” Greek genocide scholar Vassilios Meichanetsidis told Al-Ahram Weekly.

In 1935, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, its first president Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, ordered the building to be transformed into museum. While many consider it to be a “good” decision, Meichanetsidis thinks that it was actually another desecration of a historic non-Muslim place of worship. “Churches are built as churches and not as mosques or museums,” he said. On Tuesday, while speaking to a congregation at a church in Istanbul, the leader of the Greek Orthodox Church, His Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, warned that if Turkey persists with plans to reconvert Hagia Sophia into a mosque, it risks turning Christians against Muslims.

RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT ON TURKEY’S MINORITIES: Let’s not forget that Turkey and its predecessor, the Ottoman Empire, have a century old history of genocide against Greeks, Assyrians and Armenians, who constitute minorities in the country today.

According to the US State Department’s report, the Turkish government continues to limit the rights of non-Muslim religious minorities, especially those not recognised under the government’s interpretation of the 1923 Lausanne Treaty, which includes only Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Christians, Jews and Greek Orthodox Christians.

The Armenian Apostolic Orthodox community elected a new patriarch in December. “Members of the community and rights organisations criticised [Turkish] government interference in the election process. Minority communities continued to object to the prevention of governing board elections for religious foundations,” states the US report.

Another violation towards the Armenian minority mentioned in the report is the incident of forced conversion of a 13-year-old Armenian Orthodox child to Islam on a programme broadcast live by a televangelist on Turkish TV, during the Holy month of Ramadan last year, without his parents’ permission. “Members of the Armenian community and members of parliament (MPs) denounced the action,” states the US report.

Professor Anahit Khosroeva, senior researcher at the Institute of History of the National Academy of Sciences in Armenia, thinks that this is not the only case. “It mainly takes place among the citizens who left Armenia and got married to Turks or Kurds, according to statistics. I know several other cases of converted Armenian women over recent years. However, although all these cases have been widely publicised in the Turkish media, conversion is not a normal phenomenon among Armenians,” she said.

Khosroeva holds the community’s officials partly responsible. “The role of the Armenian Patriarchate in Constantinople should be significant here. Because it is known that Armenians are not so welcomed by the government of Turkey, especially the refugees, and their children cannot attend public schools. In addition, Armenians are isolated from the traditional community. It’s here that the Patriarchate must show its role by integrating these people into community life,” she told the Weekly.

The US report also states that “according to media reports, isolated acts of vandalism of places of worship continued to occur,” noting a February incident when an unidentified person or persons sprayed graffiti on the Surp Hreshdagabed Armenian Church in the Balat district of Istanbul with derogatory messages on the door and walls. “Police had opened an investigation and received security camera footage of the incident. HDP MP Garo Paylan condemned the attack. According to the community, the perpetrators had not been found by year’s end,” states the US report.

Khosroeva thinks this, too, is not new. “Vandalism against the Christian sanctuaries and culture, in addition to a continuous disrespectful attitude towards the feelings of [Christian] believers existed before the Ottoman genocide of Christians, between 1914 and 1923, and unfortunately it still exists. It’s very offensive for citizens of the same state or country to see notes on the walls of their churches full of hatred, or emptied garbage cans at the entrance of an Armenian church in Erzurum, where also unknown people left a note saying ‘Erzurum residents, this is our homeland,’” Khosroeva told the Weekly.

In March, President Erdogan raised the possibility, during a televised interview, that the status of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul could be changed from a museum to a mosque, adding that the name could change to Ayasofya Mosque. The government took no action following the president’s comments.

The US report also mentions that in November last year, the Council of State (the highest administrative court) ruled a former church and mosque now serving as Chora Museum should be returned to its status as a mosque. The museum, famed for its mosaics and frescos depicting Christian imagery, was originally constructed and repeatedly renovated as the Greek Orthodox Church of the Holy Saviour in the fifth century, and then converted into the Kariye Mosque in 1511 before becoming a museum in 1945.

“Hagia Sophia and Chora are the property of the Republic of Turkey and all means of authority [over museums] are a matter of Turkey’s internal affairs,” Turkey’s Foreign Ministry spokesman stated in response to the US report on religious freedoms, who called on the US to focus on its own domestic problems, like Islamophobia, anti-Semitism, racism and xenophobia, and not to draw the world’s attention away from US protests.

Why do Turkish authorities take pleasure in converting churches into mosques in 2020?

“Istanbul has dozens of mosques. Just next to Hagia Sophia there is the Blue Mosque and there are many other mosques across the city. I am afraid that the conversion of Hagia Sophia and Chora again into mosques represent Turkish Islamist triumphalism over Christianity and seemingly brings votes and support to the ruling party from Islamists and nationalists. In their imagination, this is what conversion represents,” Meichanetsidis told the Weekly.

Episodes of massacres and cultural attacks were the precursors to the great genocide of the 20th century. “Assyrians in Turkey, also known as Chaldean and Syriac, faced ethnic and religious persecution beginning in the mid-1800s. We have not been able to secure our own state, therefore our persecution is perpetual. The fact that the Turkish government has been denying the 2019 Report on International Religious Freedom should not come as a surprise, for the state has repeatedly denied its crimes against Christians. And let us not forget the direct involvement of the Kurds, a group which also denies their actions against all Christians, especially the Assyrians. Unless the Western countries and their allies in the region do not pressure Turkey to start honouring religious freedom and start protecting its own citizens, regardless of their faith, we will continue to witness the disappearance of the Christian community, an event which is a tragedy for all of humanity,” founder and President of Iraqi Christian Relief Council Juliana Taimoorazy of Assyrian origin, based in the US, told the Weekly.

“This is not a mentality of our times, but of some dark ages of the past, where fanaticism, destruction and barbarism prevailed. Islam is a religion of peace, respect and civilisation. Greeks and Arabs have been the initiators and bearers of religious and spiritual traditions with a universal impact,” Meichanetsidis said.

The US government estimates the total population of Turkey at 81.6 million (midyear 2019 estimate). According to the Turkish government, 99 per cent of the population is Muslim, approximately 77.5 per cent of which is Hanafi Sunni. Non-Muslim religious groups are mostly concentrated in Istanbul and other large cities, as well as in the southeast. Exact figures are not available, however these groups self-report approximately 90,000 Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Christians (including migrants from Armenia); 25,000 Roman Catholics (including migrants from Africa and the Philippines) and 16,000 Jews. There are also approximately 25,000 Syrian Orthodox Christians (also known as Syriacs); 15,000 Russian Orthodox Christians (mostly immigrants from Russia who hold residence permits) and 10,000 Bahais.

According to the US State Department report, estimates of other groups include fewer than 1,000 Yezidis; 5,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses; 7,000-10,000 members of Protestant denominations; fewer than 3,000 Chaldean Christians and up to 2,500 Greek Orthodox Christians.

Although the Jewish community in the country is diminishing, the US report states that Jewish citizens have expressed concern about anti-Semitism and threats. According to members of the community, the government continues to coordinate with them and is responsive to requests for assistance. But not all agree. “Anti-Semitism has been widespread in Turkey since the early years of the Turkish Republic. Jews in Turkey were exposed to a pogrom, their freedom of movement was restricted several times, the public use of their Ladino language — alongside other non-Turkish languages — was banned and the media targeted them extensively in the 1920s and 1930s. Today, making hostile statements against Jews and Israel is a popular trend in Turkey and it is the government that is leading and fuelling this hostility,” Turkish journalist and political analyst Uzay Bulut, who often writes about Jewish-related issues, told the Weekly.

According to the US report, the government of Turkey has continued to permit Greek Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox and Jewish religious community foundations to operate schools under the supervision of the Ministry of National Education. “Children of undocumented Armenian migrants and Armenian refugees from Syria could also attend but they were not permitted to receive diplomas, as the government classify legal migrant and refugee children as ‘visitors,’” the report states. The government has continued to provide funding for public, private and religious schools teaching Islam. “It did not do so for minority schools recognised under the Lausanne Treaty, except to pay the salaries for courses taught in Turkish, such as Turkish literature. The minority religious communities funded all their other expenses through donations, including from church foundations and alumni,” states the report.